What Are the Extent and Impact of Tobacco Use?

According to the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an estimated 70.9 million Americans aged 12 or older reported current use of tobacco—60.1 million (24.2 percent of the population) were current cigarette smokers, 13.3 million (5.4 percent) smoked cigars, 8.1 million (3.2 percent) used smokeless tobacco, and 2 million (0.8 percent) smoked pipes, confirming that tobacco is one of the most widely abused substances in the United States. Although the numbers of people who smoke are still unacceptably high, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention there has been a decline of almost 50 percent since 1965.

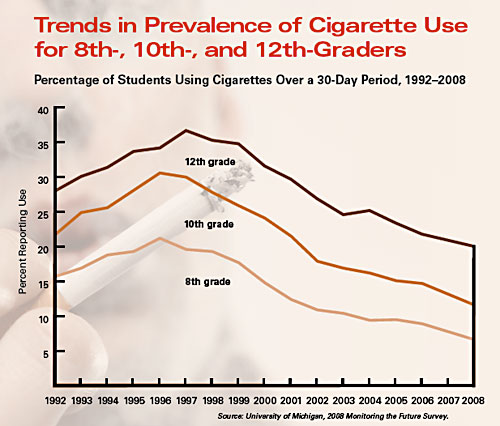

NIDA’s 2008 Monitoring the Future survey of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders, which is used to track drug use patterns and attitudes, has also shown a striking decrease in smoking trends among the Nation’s youth. The latest results indicate that about 7 percent of 8th-graders, 12 percent of 10th-graders, and 20 percent of 12th-graders had used cigarettes in the 30 days prior to the survey—the lowest levels in the history of the survey.

The declining prevalence of cigarette smoking among the general U.S. population, however, is not reflected in patients with mental illnesses. The rate of smoking in patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other mental illness is two- to fourfold higher than in the general population; and among people with schizophrenia, smoking rates as high as 90 percent have been reported.

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. The impact of tobacco use in terms of morbidity and mortality to society is staggering.

Economically, more than $96 billion of total U.S. health care costs each year are attributable directly to smoking. However, this is well below the total cost to society because it does not include burn care from smoking-related fires, perinatal care for low-birthweight infants of mothers who smoke, and medical care costs associated with disease caused by secondhand smoke. In addition to health care costs, the costs of lost productivity due to smoking effects are estimated at $97 billion per year, bringing a conservative estimate of the economic burden of smoking to more than $193 billion per year.

There are more than 4,000 chemicals found in the smoke of tobacco products. Of these, nicotine, first identified in the early 1800s, is the primary reinforcing component of tobacco.

Cigarette smoking is the most popular method of using tobacco; however, there has also been a recent increase in the use of smokeless tobacco products, such as snuff and chewing tobacco. These smokeless products also contain nicotine, as well as many toxic chemicals.

The cigarette is a very efficient and highly engineered drug delivery system. By inhaling tobacco smoke, the average smoker takes in 1–2 mg of nicotine per cigarette. When tobacco is smoked, nicotine rapidly reaches peak levels in the bloodstream and enters the brain. A typical smoker will take 10 puffs on a cigarette over a period of 5 minutes that the cigarette is lit. Thus, a person who smokes about 1½ packs (30 cigarettes) daily gets 300 "hits" of nicotine to the brain each day. In those who typically do not inhale the smoke—such as cigar and pipe smokers and smokeless tobacco users—nicotine is absorbed through the mucosal membranes and reaches peak blood levels and the brain more slowly.

Immediately after exposure to nicotine, there is a "kick" caused in part by the drug’s stimulation of the adrenal glands and resulting discharge of epinephrine (adrenaline). The rush of adrenaline stimulates the body and causes an increase in blood pressure, respiration, and heart rate.

Is Nicotine Addictive?

Yes. Most smokers use tobacco regularly because they are addicted to nicotine. Addiction is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and abuse, even in the face of negative health consequences. It is well documented that most smokers identify tobacco use as harmful and express a desire to reduce or stop using it, and nearly 35 million of them want to quit each year. Unfortunately, more than 85 percent of those who try to quit on their own relapse, most within a week.

Research has shown how nicotine acts on the brain to produce a number of effects. Of primary importance to its addictive nature are findings that nicotine activates reward pathways—the brain circuitry that regulates feelings of pleasure. A key brain chemical involved in mediating the desire to consume drugs is the neurotransmitter dopamine, and research has shown that nicotine increases levels of dopamine in the reward circuits. This reaction is similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse and is thought to underlie the pleasurable sensations experienced by many smokers. For many tobacco users, long-term brain changes induced by continued nicotine exposure result in addiction.

Nicotine’s pharmacokinetic properties also enhance its abuse potential. Cigarette smoking produces a rapid distribution of nicotine to the brain, with drug levels peaking within 10 seconds of inhalation. However, the acute effects of nicotine dissipate quickly, as do the associated feelings of reward, which causes the smoker to continue dosing to maintain the drug’s pleasurable effects and prevent withdrawal.

Nicotine withdrawal symptoms include irritability, craving, depression, anxiety, cognitive and attention deficits, sleep disturbances, and increased appetite. These symptoms may begin within a few hours after the last cigarette, quickly driving people back to tobacco use. Symptoms peak within the first few days of smoking cessation and usually subside within a few weeks. For some people, however, symptoms may persist for months.

Although withdrawal is related to the pharmacological effects of nicotine, many behavioral factors can also affect the severity of withdrawal symptoms. For some people, the feel, smell, and sight of a cigarette and the ritual of obtaining, handling, lighting, and smoking the cigarette are all associated with the pleasurable effects of smoking and can make withdrawal or craving worse. Nicotine replacement therapies such as gum, patches, and inhalers may help alleviate the pharmacological aspects of withdrawal; however, cravings often persist. Behavioral therapies can help smokers identify environmental triggers of craving so they can employ strategies to prevent or circumvent these symptoms and urges.

Yes, research is showing that nicotine may not be the only ingredient in tobacco that affects its addictive potential. Using advanced neuroimaging technology, scientists can see the dramatic effect of cigarette smoking on the brain and are finding a marked decrease in the levels of monoamine oxidase (MAO), an important enzyme that is responsible for the breakdown of dopamine. This change is likely caused by some ingredient in tobacco smoke other than nicotine, because we know that nicotine itself does not dramatically alter MAO levels. The decrease in two forms of MAO (A and B) results in higher dopamine levels and may be another reason that smokers continue to smoke—to sustain the high dopamine levels that lead to the desire for repeated drug use.

Animal studies by NIDA-funded researchers have shown that acetaldehyde, another chemical found in tobacco smoke, dramatically increases the reinforcing properties of nicotine and may also contribute to tobacco addiction. The investigators further report that this effect is age-related: adolescent animals display far more sensitivity to this reinforcing effect, which suggests that the brains of adolescents may be more vulnerable to tobacco addiction.

From the National Institute of Health