Researchers conducting a large-scale brain imaging study found clear physical signs of a familial tendency toward depression. This most recent paper to arise from a 27-year old study aiming to uncover the hereditary roots of the disorder reaches a striking conclusion: individuals with a family history of depression also display, in an overwhelming number of cases, a thinning of the brain’s right cortex.

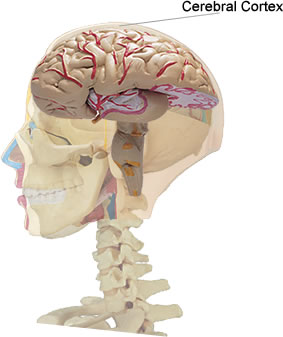

The cerebral cortex is essentially a sheet of organic “grey matter” covering the cerebrum that constitutes the brain’s outermost region and serves to both protect and inform (via neurological messaging) the underlying white matter. The right frontal cortex in particular is one of the more intensely responsive portions of the brain. It plays a central role in regulating social and emotional intelligence and corresponding responses to all forms of stimuli.

Researchers performed MRI brain imaging scans on 131 individuals, aged 6 to 54, splitting the subjects into a low-risk control group and a group whose immediate relatives had suffered from major depression. The study’s authors found that, on average, the right cortexes of high-risk subjects were 28% thinner than those of their control group counterparts; this result was unexpected and definitive.

Researchers compared this loss of organic material to the literal brain shrinkage experienced by schizophrenic individuals and Alzheimer’s patients. They witnessed the thinning trend in the offspring of depressed parents and grandparents, noting that the pattern held whether said individuals had ever actually experienced depression themselves or not. They hesitated to label the trait genetic, theorizing that it may well develop over time under the influence of a severely depressed parent – that is to say that the stresses of living through the depression of a close relative may literally wear down the cortex. A study involving children of depressed parents who were separated from said parents at birth would help to clarify the issue.

So the precise link between the thinner cortex and the greater likelihood of depression remains unclear, but a smaller protective sheath leaves the brain more fully exposed and sensitive to various social and emotional stressors, so the link makes sense. If nothing else, this study serves as final confirmation of the theory that physical predispositions toward depression exist and that they are directly related to the status of one’s parents and grandparents – whether these factors are present at birth or learned through experience.