The increasing interconnectedness of the modern world has encouraged psychologists to view each mind not as a self-contained island but as a malleable piece of a social network. The study of networks has yielded many interesting findings, such as that statistical models of nicotine addiction resemble the spread of a disease through social connections. A more positive contagion analogy appears this month in the British Medical Journal, wherein Dr. James Fowler finds that happiness spreads through friends and neighbors.

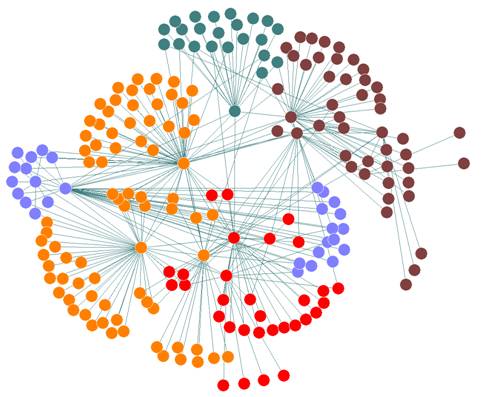

Dr. Fowler took advantage of the vast sets of data collected by the Framingham Heart Study. The Framingham study, while focused primarily on heart health, could be used for this alternative purpose because it asked participants many questions about happiness and social relations. Dr. Fowler took twenty years of data from 4739 subjects and diagramed their relations and moods over time.

Happiness was defined as a perfect score on the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale, though the authors found that lower scores would yield similar, if weaker, correlations. Observing the diagram over time, it becomes clear that happiness spreads along social connections as far as three degrees of separation. It may surprise many readers to learn that their mood can be affected by the friend of a friend of a friend. A person is 15.3% more likely to be happy if a direct connection is happy, 9.8% more likely for a second degree connection, and 5.6% more likely for a third degree connection.

Not all social connections have the same influence. Proximity and sex were both extremely important. Next-door neighbors increase happiness likelihood by 34%, but the effect of people living farther down the same block is almost negligible. This suggests that small social cues like friendly nods picked up by frequent but shallow interaction can more powerfully influence your mood than the deeper knowledge you have of best friends living in another state. In addition, same-sex transmission of happiness was much stronger than opposite sex, perhaps explaining why heterosexual partners living apart were not found to have very much influence on each other.

One possible objection to the validity of this study is that the diagrams are picking up confounding socioeconomic factors. This argument would point to the importance of proximity and suggest that people in the same neighborhoods and social circles are likely to be affected by the same larger factors like recession or gang warfare. However, this objection is significantly deflated by the fact that people living on the same block had almost totally independent happiness scores. An additional counter is that influence was much stronger for people who mutually listed each other as friends, meaning that the actual solidity of the social bond was important.

This study has important ramifications for social and business policy. When governments and employers calculate the advantage of mental health intervention or cheering events, they may be severely underestimating their value. It seems that each mood elevation ripples outward much farther than might be intuitively estimated. Hopefully, computer diagramming like this will give us a better sense of just how important a smile is.