Researchers have frequently found a correlation between amyloid-beta plaque in the brain and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). A consensus has thus been growing that amyloid beta is the cause of AD, but many scientists were wary of jumping onboard this consensus because some well-run studies detected no correlation. A study by Dr. Ganesh Shankar, published last week in Nature Medicine, explains explain the seemingly inconsistent results at the heart of the controversy.

Dr. Shankar harvested the brains of deceased organ donors to collect the four different types of amyloid-beta: insoluble, and soluble forms with one, two, and three molecules. He then injected one form or another into rats, which have served as good models for dementia in many previous studies. Some of these rats developed memory and learning deficits consistent with AD, and their brains showed significant neuron damage.

While the rise in AD cases firmly points to amyloid beta as a cause, it was only one form that raised the risk— the two-molecule soluble form. This was the first time that the forms were differentiated by any practical effect. The finding explains how some autopsies reveal brains full of amyloid-beta plaque when the patients showed no decline in mental faculties before their death.

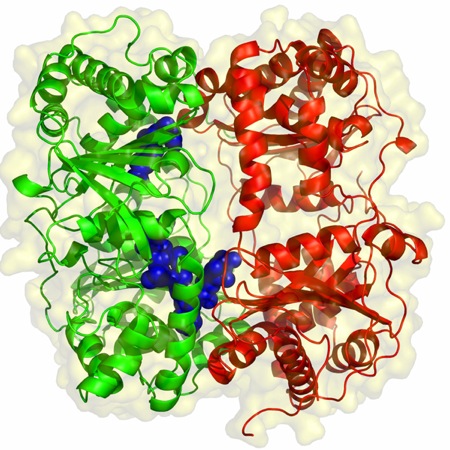

The singling out of one form is also important because it can guide researchers toward understanding exactly why neurons break down, and hopefully also toward a treatment that can prevent or reverse this process. Modeling molecule shapes is extremely difficult, but with computer capabilities advancing rapidly and with the list of culprits narrowed down to one, we have real hope of making progress.